by Lays Farra

Review of: John Matthews & Maarten Haverkamp, The Prophecies of Merlin: The First English Translation of the 15th-Century Text, Inner Traditions, 2025.

For convenience’s sake this review will refer to one of the Vérard editions available online, often with links to images of the page discussed, as they have the same content and page numbers as the princeps edition. Translations are mine and might be a bit too literal when trying to show the translation problems of the Matthews/Harvekamp book. Comments or corrections welcome at: contact@sursus.ch.

Despite writing books purporting to be an expert in arthurian literature and legend, with titles as presumptuous as “The Complete King Arthur”, Matthews shows an impressive lack of knowledge and, even worse, curiosity, about all aspects of arthurian scholarship, even some that are pretty elementary and should be grasped by any amateur, let alone an “arthurian scholar”.

This shows how an occultist bent can warp the human mind: everything must be connected to ancient celtic wisdom or, more widely, anything deemed sacred and profound, too often at the price of one’s capacity to reason or even read what’s in front of oneself.

This latest installment purports to be a translation of Antoine Vérard’s 1498 edition of the Prophecies de Merlin, a complex arthurian text whose roots go back to the 1270s. This was a bad idea from the start as this edition is a particularly complex specimen in the manuscript tradition (as we will discuss shortly), and even the best editor or translator would struggle at many points in the endeavour. But this book cannot even qualify as a straightforward translation of Vérard’s edition. Apparently, it was translated by Maarten Haverkamp, somehow, with so many translation errors and incongruities that I doubt the ability of everyone involved to understand French. I suspect machine translation or transcription must have been used at different points, even though I don’t see how machine translation would even make some of the mistakes we will discuss below. This translation was then rearranged, the order of episodes changing in a way that I honestly do not understand, as it doesn’t fit the printed edition, nor the manuscripts, nor human logic — and then patched up with other texts, like summaries from Paton’s edition of the Prophecies de Merlin (not realising, it seems, that the texts she was summarizing have been edited in full multiple times since).

So beyond the blatant errors and omissions in the commentary, it is simply not a linear translation of Vérard’s edition of the Prophecies, as promised on the cover, which most readers would have no way of knowing. And unless you take the time to do a full comparison to Vérard’s edition (as attempted below) and are able to read Old French, it would be quite impossible to realize the extent to which the text has been garbled, being a very disorderly member of an already complex manuscript tradition.

It’s quite difficult to justify bringing such a text to the English-speaking public. There might even be a word for that.

The translation contains repeated, egregious errors, on every page

My guess is that Haverkamp, who passed away this year as the book was about to be published, somehow produced a translation (maybe with some help from machine translation) that Matthews rearranged (“put together”, he says) as he saw fit without much verification. Notes such as “Trans. by Caitlín Matthews from the original French text included by Paton in her edition of the Prophecies.” (p. 23) indicate a more collective endeavour, but not a better one. John Matthews’ acknowledgments go “To my wonderful wife, Caitlín, for spending so much time checking every word and making sure she caught the howlers!” while Maarten Haverkamp’s mention he has worked for five years on the book. (p. 279) Despite all these efforts, we will discover plenty of “howlers”, so much so that I will physically be unable to list them all, but the sheer magnitude of the issues will soon be apparent.

I should emphasize that Vérard’s text, as can be the case for these early printed editions, is in a pretty sorry state and can often be in need of correction itself. For one example, there’s a prophecy about Segurant:

“[…] ne sera ja achevee pour nully fors seulement pour la chaleur du dragon qui de soy fera quintaine a la court du roy Artus” (CXXXVIr)

Literally: It will be accomplished by none except by the heat of the dragon who will make a quintaine out of himself at the court of king Arthur

But this refers to the story of Ségurant, who, at the tournament of Winchester takes the place of the quintaine (a mannequin used in tournaments that would be struck by knights on horseback) showing his mastery by tanking the assaults of every other knight without being able to maneuver or take some momentum etc. So even though “the heat of the dragon” works on a surface level, we know it to be corrupted, either:

- Le chaceur du dragon (the hunter of the dragon) became la chaleur du dragon at some point. (Arioli 2016:81)

- Since he hunts a dragon, Segurant is known as the Chevalier au Dragon (Knight of the Dragon) and thus it’s possible that the abbreviation for chevalier, chlr, was misinterpreted as chaleur. (Arioli 2019:II.165)

So, when we do not know the story behind an allusion (notwithstanding when it is edited by people that mostly don’t know these stories) it’s quite complicated to assess if the text is simply enigmatic or actually faulty. The Dictionnaire de l’ancienne langue française by Godefroy even quotes this passage among his examples for the word quintaine.

With that in mind, let’s start reading the translation.

The first chapter already contains egregious errors. Tholomer asks Merlin what he’s thinking about. The translation says :

“I think of the people of the world who left Jerusalem 277 years ago.” (p. 55)

A note adds : “We assume this refers to the Hebrew nation as a whole”. But the actual text doesn’t talk about people but about the thing that was born in parts of Jerusalem (more on that next paragraph). And not 277 years ago. The actual text and translation would be:

“Je pensais aux terres qui seront parmy le monde au temps que la chose qui jadis naquit es parties de Jerusalem aura mil deux cents LXXVII ans” (Ir)

I was thinking about the lands that would be among the world in the time at which the thing that was born yesteryear in parts of Jerusalem will have 1277 years

We’ll see that numbers are regularly misread (forgetting the word mil, here, mille = one thousand), so not when the thing has left Jerusalem 277 years ago but when said thing will be 1277 years of age, The Thing that was born in parts of Jerusalem, referred to time and time again in the Prophecies de Merlin seem to designate the Church of Jesus Christ. E.g. the period when the tireurs de cordes hold sway over the “governor of the thing that was born in parts of Jerusalem” refers to the vacancy of the Papacy. (Paton 1927:II.176)

Thus the prophecies that mention its age actually count back from the birth of Jesus, and thus the number refers to the actual year in the christian calendar at which the prophecy will occur. For example, the one in Paton LXXXVI talks about a champion that will die excommunicated (Frederick II) and he had a son who was a buisart (harrier) but believed to be a falcon, and who will be held almost all his life in jail. Antoine asks: When will this happen? Merlin says, when the thing that was born in parts of Jerusalem would have passed 1248 years and a half. This probably refers to Enzio, Frederick II’s ambitious son, who was in jail from 1249 until his death in 1272. (Paton 1927:II.5) These number of years since the thing was born thus refer approximately to the actual year of the event. A lot of these references are situated in the years 1272-1279 and actually allow us to give this as a probable date for the redaction. (This makes it even more misguided that they keep repeating that the Prophecies de Merlin dates from 1302.)

The rest of the chapter seems to cut parts of the Vérard edition as well but let’s skip a little afterwards.

“And I tell you that at that time the clerks in Telz* will sin as I said.” (p. 57)

The note indicates : “Telz is a township in Lithuania, associated with sects regarded as heretical in the Middle Ages” But this is complete nonsense: in the context, the word obviously and simply means tel, that is the french word for such.

Et si te dis je que en celui temps seront les clercs en telz pechez comme je faitz mencion. (Iv)

And thus I tell you that in that time the clerics will be in such sin as I have mentioned.

Further along :

“Merlin,” said Master Tholomer. “The other people of the world, how will they be at this time when things get worse? Because even their temptations are written in your prophecies.” (p. 57)

Wrong again, the end is actually

pourquoy seront ilz en cellui temps si empirez ? Car toy mesmes les as fait escripre en tes prophecies

Why would they end up worse in this time? Because yourself made it put in writing in your prophecies

Not sure why it becomes about temptations.

The governor’s court will grow worse from that time until the Thing that once left Jerusalem shall be one thousand, one hundred, and twenty-three years old—not in the knowledge of all men, but amongst the clergy. (p. 57-58)

Here we see the thing that left Jerusalem, a theme mistranslated before by “people”, but now they get it right, while getting, again, the number wrong. Let’s look at the french text again :

La court du gouverneur yra en empirant des lors en avant que la chose qui jadis nasquit es parties de Jerusalem aura mil cent .iiii. vingtz neuf ans, non pas au [IIr] sceu de toutes gens mais en repostz entre les clercs.

They give 1123 years old, but it’s actually 1189 years old. French has some weird way to count numbers nearing a hundred. 80 is quatre-vingts (literally four-twenty, that is four times twenty) — in mainland France at least, french speakers in Switzerland and Belgium have huitante or octante. So in this old edition you get mil (mille = 1000), cent (100) .iiii. vingtz (quatre-vingts = 80) neuf (9) → 1189 years. Why this mistake? I assume it’s related to being unable to read the font of this old edition or using an unreliable and automated way to transcribe or translate it. The z at the end of vingtz (twenty) does look like a 3, thus vingtz could become twenty-3, and thus 23. The word neuf could be ignored (in an automated translation it could get lost as neuf also means new), thus leaving us with 1123.

The next section skips a bit of the first column of fol. IIr to keep mistranslating.

“Explain, Merlin,” asked Master Tholomer. “Is there hope of Heaven in the sky?” “Yes,” he said. “And I can hear the words that are said in the Holy Church, to which the firmaments under Heaven give structure.” “Dear God!” said Tholomer. “I believe that you are so perfectly full of knowledge that no man in the world would dare dispute these celestial facts.” “Of course,” said Merlin. “None of the clergy from this century have dared to do this. It must be done only for those on whom the Holy Spirit takes pity.” (p. 58)

Here is the original text and my translation:

Dy moy, Merlin, fait maistre Tholomer, est point aucune eave dessoubz le ciel ? — Ouy, fait il, et si le peux appercevoir aux paroles que Yon dit en sai[n]cte eglise,.que l’on dit que les eaves qui sont dessoubz les cieulx donnent louenge. —Se m’aist Dieux, je croy, fait Tholomer, que tu es si parfaictement plain de science que nul homme du monde ne pourroit avoir vers toy duree a disputer des faits celestiaulx. — Non, de vray, fait Merlin, tous les clercs qui jadis furent au siecle ne qu’ilz doibvent advenir fors seulement ceulx qui furent plains du Saint Esperit ou ceulx qui adviendront que le Sainct Esperit mettra en eulx. (IIr, corrected by Paton 1926:I.452)

Tell me, Merlin, said master Tholomer, is there any water under the sky? — Yes, he said, and one can notice it in the words that are spoken in the holy church, as we say that the water beneath the sky give praise. — God help me!, I believe, said Tholomer, that you are so perfectly full of knowledge that no man in the world would last in a debate against you about the facts of the heavens. — No, for sure, said Merlin, all the clerics that existed in the past in the world wouldn’t, nor would those that would come later except those that were full of the Holy Spirit, or those that will come and that the Holy Spirit would put [Himself] inside them.

Easy mistake here: siècle, does mean century in french today, but au siècle could mean in the world as it refers to the worldly sphere of existence, as in the word secular. I think the water dessoubls les cieulx refers to Psalm 148, verse 4, that talks about waters above the skies (instead of under), that do offer praise! In King James’ Bible: “Praise him, ye heavens of heavens, and ye waters that be above the heavens.” The latin vulgate gave: “aquæ omnes quæ super cælos sunt ipse dixit et facta sunt” and the Psautier de Metz (14th c.) has “Loeiz lou li ciel des cielz et toutes yawes dessus les cielz”. (Toynbee 1892:301) Dessus (over/atop) must have become dessous (under) at some point in the transmission of the text.

That said I do not know why water becomes hope and firmaments here. I’m lost. I’m losing my mind.

At this point, we’re a few pages in, and already under a firm impression that Matthews&co do not understand anything about anything. But garbling the sacred word of God is one thing, now comes another transgression: the garbling of arthurian literature.

First up a very revealing hodgepodge about the death of King Lot:

“Write that King Lot of Orcanie will be killed because of his pride after the coronation of King Arthur. That he killed his son out of treachery. Those who will kill their father are sons of the same King Lot.” (p. 59)

This is actually a very well known episode: in the Post-Vulgate Suite du Merlin, King Lot is killed by Pellinor during his rebellion against Arthur. His son, the young Gawain (aged 11 at his funeral) swears he’ll avenge this murder. A few manuscripts (BL add. 36673 fol. 237r-v, Turin L.I.7 fol. 216r-217v) even develop the story of Gawains trecherously killing Pellinor as discussed by Fanni Bogdanow in a 1960 article, editing the London text.

The french text of Vérard’s Prophecies is a bit convoluted but perfectly clear:

“Or metez en escritp que le roy Loth d’Orcanie mourra & sera occiz par son orgueil après le courounement du roy artus. Puis occira un sien filz en trahison Celluy que son pere aura occiz et ung fils de cellui mesmes que ie je dis de cellui roy loth.” (IIv)

So write down that the King Lot of Orkney will die & will be killed through his pride after the crowning of King Arthur. Then one of his sons will, by treason, kill the one who had killed his father, and one son of that very one that I said, of this King Loth.

Pellinor killed Lot, Gawain will kill Pellinor. No mystery. Unable to account for this misreading, and apparently unaware of the Post-Vulgate (as we will see in the next section again) they invent an unknown episode where Lot and his sons murder each other (they read fils as a plural it seems), and keep digging into nonsense in their commentary:

“Next, he mentions King Lot of Orkney, a familiar character from the Arthurian cycle. Married to one of Arthur’s half sisters— Morgause—he is the father of the famous knights Gawain, Gaheries, Agravaine, and Gareth. The story referenced here is unknown elsewhere. As far as we know, Lot did not kill his son, nor did his sons slay him. He was, initially, an adversary of Arthur, being one of the eleven kings who rebelled against the young king following his withdrawal of the sword from the stone. In the Merlin Continuations, which follow the Lancelot-Grail cycle, Lot allies himself with King Ryons and King Nero to attack Arthur, but Merlin distracts him by visiting him and weaving an elaborate set of prophecies about his future.” (p. 141)

About Galahad: “And the water from the fountain will stop flowing when he puts his hand in it.” (p. 60)

Non, la fontaine bouillonnante cessera de bouillonner. cf. 1498:IIv boiling, or bubbling, not flowing.

“I hope you also write down,” said Merlin, “that with the granting of judicial equality, there will be less kindness and courtesy for all of the knights from the king.” (p. 60)

Granting of judicial equality ? The french text simply says

“Depuis que celle grant cour fauldra il ny aura par tout le monde entre les chevaliers de la crestiente la moictie de la loyaulté ne de la bonte ne de la courtoiisie qu’il y avoit en celle de cestuy roy.” (1498:IIIr.)

When this great court will fail, there won’t be accross the whole world among the knights of christendom half the loyalty nor the goodness, nor the courtesy that there was in the one of this king.

Grant court simply means Big court or Great court, the court of King Arthur, saying that when it will disappear, there won’t even remain in the rest of the world half the loyalty, goodness or curtesy that could be found in his court. In what seems an automated translation, once again, grant, is not translated as big or great, but read as the english world grant and court was interpreted as a judicial court — which is often the case in LLMs because these days, it’s more usual to discuss tribunals rather than royal courts — and therefore became judicial equality. Insanity.

From Or mets en ton escript (1498:IIIra) the translation cuts a prophecy about the Thing That Was Born In Parts Of Jerusalem, although a few different passages talked about it already before, some of which the authors managed to read (p. 58) to instead give a few episodes inserted here for reasons quite mysterious to me.

- Merlin discussing the dragons under the tower of Vortigern with Uther. In the Vérard edition this episode is only found quite later in fol. CXLIIv-CXLIIIr

- “Then Merlin said: “There is a sword in the serpent-stone at Monte Gargano, and from the mountain no one can take it out except the chosen one.” (p. 61) The commentary then goes : “Merlin then adds an even more intriguing note: “There is a sword in the serpent-stone at mountain Gargano, and from the mountain no one can take it out except the chosen one.” This is a most interesting comment to find here. It refers to a story associated with a Saint Galgano (c. 1148–1185), attached to the town of Montesiepi in present-day Tuscany, where a sword stuck fast into a stone is still shown. Though this is almost certainly a fake, it reflects a very interesting story, which may be summarised as follows.” (p. 145)

- This seems, to me, to be a pure fabrication, the Vérard text only mentions that Uther was asking Merlin how the two dragons under Vortigern’s tower could survive underground, Merlin makes him bring a rock and split it by masons, a small dragon with very shap teeths exit, and Merlin catches it, showing a dragon can live in a rock, as is the case of a serpent qui est au mont gargans, another snake (dragon) at mount Gargans, that is trapped in a rock and eats through the rock, and will end up exiting it, growing wings and causing havoc. A nice story. I have no idea where this added sentence comes from. But transforming Gargans to Gargano to connect it to the sword of Saint Galgano, sometimes cited as the origin of the sword in the stone seems, to me, quite in line with the Matthews brand.

- The visit of the Queen of Brequehem (they assume it means Bethlehem, because they must connect everything to the little sacred history they know) :

- One day Merlin received a visit from the Queen of Brequehem, and he said to her: “There will be natural disasters and unusual events in the Holy Land, and wars, and famine in Treviso. Write on, Tholomer, write that government and the church will become corrupt and follow a false religion.” (p. 61)

- Not sure about the source. The Queen of Brequeham (Paton LXXI sqq.) or Berkeham (Koble IX) is found elsewhere, but Merlin, invisible, only gives her a remedy for her lust.

- The coming of the Emperor before the Pope with a hundred knights. This last one is cut with an “Editor’s note: This section is moved to section 70, where it clearly belongs.” but in Vérard’s edition this text is already found way later at fol. XXVI. It feels like Harvekamp already reordered the material, and Matthews picked up after him, correcting disorders he thought came from the edition.

- Short prophecy about the death of King Arthur killed by his son-nephew. (a quite longer and different exchange about the death of Arthur but not Modred is found in Vérard Vr, not sure where this one comes from)

I do not know why these texts are inserted here. I thought, maybe to regroup the Tholomer-episodes or something like that? But the story of Uther and the dragons is told to the Sage Clerc, a later scribe in the story, not Tholomer. (see CXLIIvb)

Then the visit of the Damsel of Wales to Tholomer and Merlin corresponds to Paton chap. III (I.60) (adding the phrase “She has the mark of the supernatural”?), until this sentence happens :

““I see,” then said Merlin, “the Holy Grail traveling from Jerusalem to Babylon and again back to Jerusalem, and I see it wandering many times afterwards, and many will go in search of it. Eventually, I see that the Holy Grail will be guarded along with a bleeding spear in an inaccessible castle, guarded by the Grail king and the Grail knights. The Grail is said to provide happiness, eternal youth, and food in infinite abundance.”

I’m not sure where this passage comes from as you’ll not find it in this Vérard page or the Paton edition at this point. Furthermore, this last sentence seems to be a gloss that should be in a footnote and was left in the text?

Then we come back to the end of fol. IIIa of the Vérard text :

“Now write down that because of the Thing that came out of Jerusalem one thousand, two hundred, and seventy years ago, there will be heavenly miracles. Our Lord wants us to know that he will be angry, and when you say this, the world will tremble with love, and when you say that innocent blood will suffer evil, it will be there.” (p. 62) etc. IIIiv.

(Getting the number of years right for once, by the way.)

Merlin mentions descendants of Isaac who will be killed because there are cannibals among them, Tholomer asks why those guilty of cannibalism and those that aren’t would be both killed, Merlin answers: because they have done nothing to prevent it, etc. Then he asks if this people will join the Dragon of Babylon. In the translation the question is wrong, and Merlin’s answer is cut:

“Tell me, Merlin,” asked Tholomer. “Will the Dragon of Babylon throw some kind of great feast?” “No,” said Merlin. [ . . . ] (p. 63)

Throwing a great feast? From what I can gather the actual text says something like:

“Dy moy merlin ce dit tholomer y aura il de celle gent avec le Dragon de Babilonne grant partie? ils feront presque les dixiemes parties moins.”

Tell me Merlin, said Tholomer, will these people make up a great part of the peoples joining the Dragon of Babylon ?

They will make up for around less than the tenth [of his troops]

They didn’t understand it and therefore cut it? Partie which means part seems to have been interpreted as the english party.

“I want you to write that a man will come to Babylon, and it will be that man who was born a minor in a place near the Indies. That man will calculate the coming of the Dragon to be thirty years. He will make many people believe that the Dragon is the Messiah.” (p. 63)

“Born a minor”! Instead of born an adult? The text says he will be born near the Indes la mineur :

viendra ung homme en babilonne et sera cellui homme ne en envalinee aupres des indes la mineur (IIIv)

I would hazard a guess that this refers to India Minor, the small India. In ancient geography, it referred to the Indian ocean near Ethiopia or Egypt, by opposition to India Major, India proper. (Cf. Muckensturm-Poule 2015) But in the Middle Ages, it could shift. While India Major could be India proper, Middle India the Indus, central Asia, etc. and India Minor Southeast Asia, in Marco Polo (Le Devisement du Monde, 1298-1307?) the mendre Ynde (Lesser India) seems to go from the Indochinese peninsula to the Bengal while Ynde greignour (Greater India) seems to be around the Malabar coast, and the moienne Ynde (Middle India) refers to Ethiopia. In the Mirabilia Descripta (1329–1338) of Jordan Catala, India Major is mostly what we call India (and beyond) while India Minor refers to the region of Pakistan, Afghanistan and Iran. (Gadrat 2005:131)

[Addendum, 30 dec 2025 : the Inde le Major is mentioned in the Chanson du chevalier au cygne (v. 319), about the battle between Alexander and Porus. Claude Lachet’s edition (2023) adds a note by Jacques Le Goff : « L’Inde Majeure, qui comprend la plus grande partie de notre Inde, s’encadre entre une Inde Mineure qui s’étend du nord de la côte de Coromandel et englobe les péninsules du sud-est asiatique, et une Inde Méridienne, qui comprend l’Éthiopie et les régions côtières du sud-ouest asiatique. » Jacques Le Goff, « L’Occident médiéval et l’Orient indien: un horizon onirique », Pour un autre Moyen Age, Paris, Gallimard, 1977, p. 291.]

This keeps going:

« Then Master Tholomer wept openly, and Merlin said: “Now I pray you go live as you promised me. I shall not come to Wales just to speak. I want you to say that you heard me crying loudly.” And Master Tholomer answered and said: “I will seem to be on fire [with inspiration] while you are with me » (p. 64)

Wrong again:

Je veux que tu dies que tu m’a ouy tesmougner dung grant fait » (IIIv)

I want you to say that you heard me testify of a great deed/fact

Not “cry loudly”. Once again the commentary leaps from that, high on their own supply:

“This seems to upset Tholomer greatly, especially when Merlin adds that he will not come to Wales himself but wants Tholomer to say that he has “heard him crying loudly.” This can only be a reference to the Cri du Merlin, the voice of Merlin that echoes from within his tomb and is thus the first mention within our text of the prophet’s impending doom at the hands of the Lady of the Lake.” (p. 150)

Same goes for Tholomer

Je seroie tout prest apparille dentrer en ung feu au tant comme tu as este aevcques moy et que tu me comptasses de maints faits

I’m not sure but might be something like: I would be fully ready to enter in a big fire, [as long as] you stay with me as you did and you recount many deeds to me

Confusion endures after that:

“And if there comes no other prophet to proclaim this, you alone will have declared this. To confirm these things, another scribe must take my book, read what is written there, and decide whether or not you truly foretold these things.” (p. 64)

In fact, Tholomer simply says that if someone came and doubted him he would only need to check in the books, but doesn’t speak of the coming of another scribe.

Here we might have another failing from automated transcription or translation?

“Master Tholomer,” said Merlin, “I am not telling anyone I’m dying” (p. 64)

Let’s go back to the original french:

“Maitre fait Merlin. Je ne dis pas a nully que je croye que je die vray. » (IIIv)

Master, said Merlin. I do not say to anyone that I believe that I tell the truth.

It’s a bit convoluted, but in essence Merlin says: no need to tell them that I tell the truth, and follows up by saying: if they do not believe me they just have to wait and my prophecies will turn out to have been true. (Our esteemed translators mistakenly think that he talks about believing in the Dragon of Babylon here) So why does telling the truth becomes I’m dying? Well, as you have seen, in this old orthography, dit is written die. And it seems, like the grant court and the partie before that, it was read as if it was the english word. The french dit was interpreted as if it was the english die.

Again, this appears to be the mark of an automated process that would keep the meaning of english words. (Or a translator that keeps forgetting english is not french.)

Once again, another passage not there in the Vérard edition:

“I want so much to speak directly to God, just like you,” [said Master Tholomer]. “Soon you will go to Wales,” said Merlin. “Eventually, you will become bishop there. But you will never see me again.” Then Master Tholomer kissed Merlin good-bye,

Not sure where it comes from either, but Merlin does say that he will never see him again… in Ireland. (IIIva) They have to leave Ireland, and Tholomer has to go to Wales to put in writing all his prophecies. Merlin tells him to come as he had promised, he refuses, but, as I understand, Merlin says that he will see him in Wales? That’s what happens afterwards at least, Merlin goes to London but he comes to see him as soon as he got there almost :

« Tholomer avoyt fait ellire vingt et deux chanones en galles. Cellui jour mesmes vit merlin et lui dist […] » (IVr)

The next part follows Vérard IVr, until:

“[…]and after a long life devoted to God, he finally died in the Holy Land. But before he left, he gave the Book of Prophecies to Master Antoine, who wrote down everything in a new book.” (p. 66)

Not here in Vérard either.

Then chapter 8 is supposed to insert an excerpt from the Rennes manuscript about the prologue of Master Richard, presenting himself as the author of the Prophecies de Merlin. It comes indeed from Paton’s edition (I.76) but if you read her footnotes you will see the text actually comes from the manuscripts “[BnF] 350, [BL] Add. [25434], B [Bern], [BnF] 15211, [BnF] 98, A [Arsenal], C [Chantilly], and the Italian versions”, hence why it’s in small type between rubrics.

But the last phrase, as becomes usual comes from who knows where:

“And at that time poor people began also to speak more about Merlin’s prophecies.” (p. 66)

The following chapters seem more in line with the order of prophecies in Paton.

- Chapter 9 about the crown of the emperor of Orbance follows in Paton (XIV) but corresponds to Vérard LVII?

- Chapter 10 about finding said crown follows Paton XVII, still managing to collapse some sentences “par toute l’isle et par toute Esclavonie” becomes “all the Islands of Slavonia”. (p. 67, it should be “across the whole island and across all of Slavonia”).

- We skip Paton XVIII, but chapter 11 “How a large part of India will melt”, corresponds to Paton XIX, “D’une grant partie des indes qui fondra” (I.78) — but is found way later in the Vérard edition, at fol. CXXIIv.

- We skip Paton XX and XXI, chapter 12 follows Paton XXII, about the evil Lady of Fallone (I.80), who, again, appears way further along in the Vérard edition at fol. CXXIIIr.

Enough.

The text starts at page 55 and we have strenuously arrived around page 69 for a grand total of 15 pages. I started filling a table with the correspondance between this translation, the editio princeps, and Paton’s edition to give an idea of the seemingly random order of the translation, but gave up after many hours. Empty cells and misplaced texts whose source I haven’t found yet are therefore left as an exercise for the reader.

I simply cannot do a line-by-line commentary for the whole book, it would require redoing the whole translation altogether and navigate the whole tradition of the Prophecies de Merlin. I’m sure the source for the displaced passages might be found, sometimes easily even, as I’ve found many, but I do not dispose of unlimited free time at the moment, and the productivity of such an exercise declines quickly when every page reveals the same problems.

A few bonus ”howlers”, found simply trying to match the texts with the editions and manuscripts:

p. 78 : About Meliadus, lover of the Lady of the Lake : This will refer either to Meliadus, who is the Lady of the Lake’s lover in our text, or to Accolon of Gaul, who has the same role in other Arthurian texts (p. 78)

The commentary specifies la Suite de Merlin (Post-Vulgate, it must be said), and Malory. But it’s wrong: in both, Accolon is the lover of Morgana and not the Lady of the Lake.

p. 86 : “Galeholt, or Galehaut the Haut Prince, is a companion to Lancelot who dies by his own hand when the latter fails to acknowledge his love. Some of his adventures are told within the 1303 text of the Prophecies.”

Galehaut basically dies of a combination of disease and heartbreak rather than suicide.

p. 89, they note that “Hugon Sachies is An unknown character only mentioned in this text. It literally means Hugo the Wise.”

That is not true, Sachies would be the imperative form of savoir, (sachez in modern french), in context:

“les lettres de la pierre ronde que le chevalier trouva au cymitiere Du roy hugon / sachez certainement que je les entaillay de mes propres mains” (CVIv)

« the letters of the round stone that the knight found in the cemetery of King Hugon. Know with certainty that I engraved it with my own hands »

p. 90 : « Meliadus went first straight to Antoine, the Wise Clerk of Wales »

Antoine and the Wise Clerk are two different characters, what gives?

p. 97 : A demon interrogated says “Sir Chaplain, we have lost Merlin and will continue to lose him. He is considered part of the Supreme God.”

Se tenir de la partie (CLIr) means being in the same camp as God, not being part of God.

p. 100 “When the Round Stone reached Burma”

Note: “Although both India and Burma were known by this time, the actual name should be seen as a reference to Berne in Switzerland.”

Why? Who cares. Being swiss I take it as a personal insult.

p. 108 : ““Do you not know that he sent me to Tous Saints?” said the damsel.”

With the fiery confidence of the incompetent, a note adds: “All Saints. Another unknown location.” No! She says that Merlin had sent her to India on All Saints Day two years ago! It’s a date, not a place! (Time seems to be distorted as she was sent away during the reign of Uther decades ago but only two years seem to have elapsed for her, that’s the point of this story!)

Then:

“Dear God, he is lost!” said the king. “He has been dead more than fifteen years.” [he actually says sixteen]

“My God!” she said. “Merlin has not been in my life for so many years.”

The total opposite. She actually says : I’v seen him just two years ago.

p. 111 : King Arthur has a nephew called Uther which is confusing but Matthews&co are further confused because Uther is dead and they missed the part where there seems to also be a nephew called Uther. Admittedly it is pretty confusing and might be the result of a fault in transmission.

p. 116 : a note says that the name of Orberice comes from “This place name comes from the river Orbe, a tributary of the Rhine that rises in France and flows to Switzerland, where it forms the river Thielle at its confluence. The similarity of the name to Orbance may have suggested this.”

Again I take this personally, I thought that insane arthuriana related to swiss placenames was limited to Charles Musès’ infamous article in the JIES.

chap. 85 p. 125 : “I’ll tell you,” said the Wise Clerk. “I have studied the arts of energy for a long time, and if I have learned anything, I believe that all the senses of the world are hidden in this cave. Merlin is so powerful that he has even travelled back in time to explain the dreams of Caesar, ruler of the Roman Empire.”

A note explain that time travel is unnecessary as they are somewhat contemporaries. I haven’t come upon the source of this text but I’d wager that every single word is wrong.

The introduction reveals the shallowness of the authors’ expertise

It seems unlikely that they actually read Paton in depth, and seem to misunderstand everything they have read. Having understood that her edition is based on the Rennes manuscript, but failing to understand that her edition collated many more manuscripts (e.g. p. 18) they call it « the original manuscript of the Prophecies dating from 1303 » (p. 51) or “the first Prophecies of Merlin in 1302” (p. 113, 211) while recognizing that earlier versions must have existed. (p. 18)

« However, we were delighted to discover that the Vérard version contains more of the original structure and content than any of the previous volumes. » (p. 19)

This is an unfortunate way to put it, even only taking into account Paton’s theories, notwithstanding the scholarship written since.

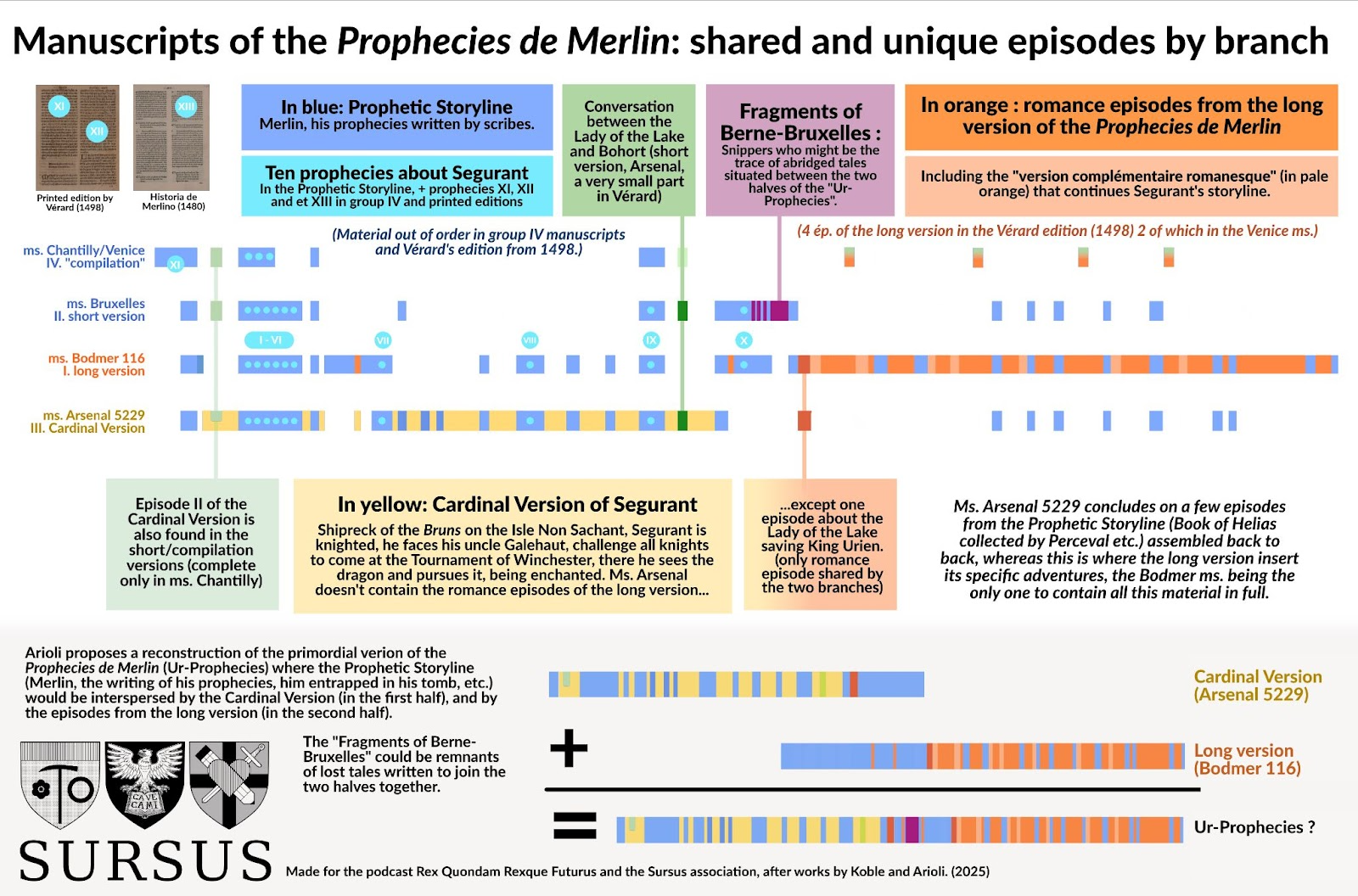

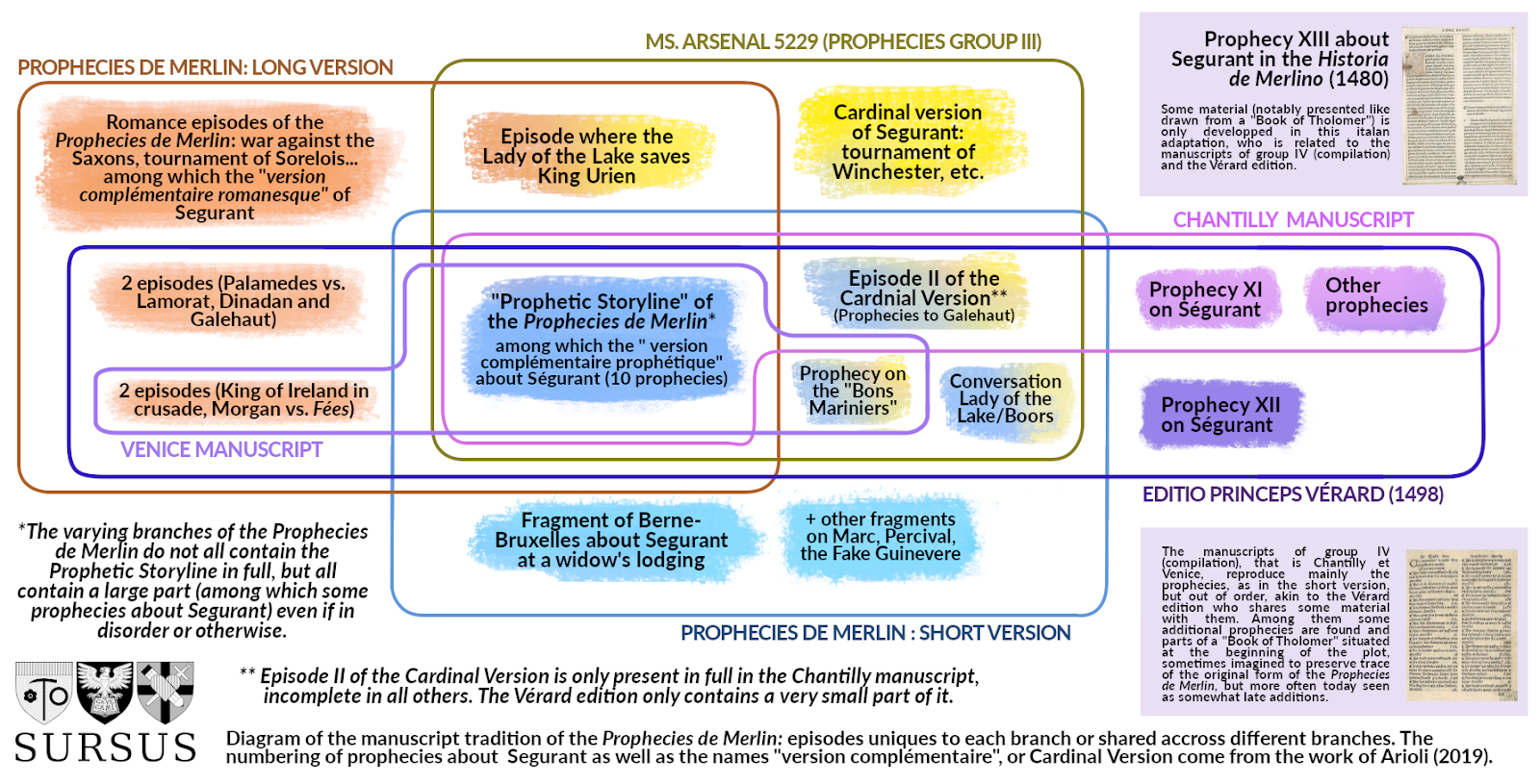

There is a long tradition of prophecies attributed to Merlin, in Geoffrey’s Historia Regum Britanniae and the welsh tradition, but here The Prophéties de Merlin designates a french novel, probably written in the 1270s in northern Italy, as is the case for other arthurian romances and compilations from more or less the same milieu (Rusticien’s compilation, Queste 12599, Livre d’Yvain). The common thread is centered around Merlin reciting prophecies to different scribes writing them down, he is then enclosed in his tomb by the Lady of the Lake but keeps prophecizing from within. Even after his spirit has left the tomb, Percival collects Merlin’s prophecies written in stone or in books. The different versions of the story might interweave different storylines to this one according to the classical technique of entrelacement, going back and forth between storylines. In a classification still held up by the field, Paton divides the manuscripts into four groups :

- Group I : the short version, focusing on Merlin’s “prophetic intrigue”.

- Group II : the long version, where arthurian episodes are interweaved at the end of the story, a war against Saxons, the tournament of Sorelois, adventures of Alexandre l’Orphelin, episodes about Segurant, etc.

- Group III : the Arsenal 5229 manuscrit does not contain the episodes of the long version, but interweaves, at the start of the story, episodes mostly about Segurant

- Group IV : “compilation”, the manuscripts in this group (Chantilly, Venise) focus on the prophecies like the short version but out of order and contain other materials.

The correspondence between these manuscripts can be illustrated by the following diagram, taken from our article about the Segurant matter, that will be available shortly in english:

In 1498, Antoine Vérard printed a version of the Prophecies de Merlin concluding a trilogy starting with the Prose Merlin and its Vulgate Suite. Fortunately or unfortunately his text seems pretty close to the weirdest group of manuscripts, group IV, and shares some material with it. For example a long section of out-of-order prophecies in the Venise manuscript is found in exactly the same order in the Vérard edition, so he must have used a related manuscript. Vérard also shares some material with the Chantilly manuscript. As the authors note, Paton called it “wildly confused” (p. 18) — not without reason. See the table in Paton I.40-1, it can also give you an idea of the disorder they are found relative to the rest of the tradition : the first prophecies corresponding to Paton’s chapters are those of chapters… CXXXVIII-CXLI, CL, CLI, CXLIV — and it doesn’t get better.

In this continuity, Merlin’s prophecies were first written down by Blaise, his mother’s confessor, like in the Merlin en prose, aftew which came a whole roster of scribes, starting with a Tholomer (seems a deformation of Ptolemy) that does not last long before being replaced by Maître Antoine. The group IV and the Vérard edition contains some prophecies that seem spoken to Tholomer, and thus could be taken from a “Book of Tholomer” situated at the beginning of the plot. (Italian translations develop this book, but they also retrofit a “book of Blaise” so not necessarily reliable.)

Furthermore Vérard contains episodes (often truncated) shared with the other groups :

- In the short version (I), the Arsenal ms. (III) and the compilation group (IV)

- Prophecies to Galehaut le Brun (in full only in the Chantlly manuscript), Vérard has a fragment (CXXVv).

- Conversation of Bohort and the Lady of the Lake (Bern 81r ; Arsenal 140r), in Vérard (LIIIv).

- An additionnal prophecy about the “Bons Mariniers” (Venitians) cf. Paton I.66-7n11, Partially in Vérard CXXVc = Venise 87d-88b.

- Finally, Vérard preserves four episodes of the “long version”, two of which are also in the Venise manuscript.

- Palamèdes facing Lamorat (Koble XXXV.15-18), even if his name is replaced by Méléagant (1498:XXXVIIa).

- Dinadan, Galehaut and Méléagant (Koble LI.8-12 = 1498:XXXVIIIa-XXXIXc)

- King of Ireland in crusade (Koble LXXIII.1-10 = 1498:LXXVIIa-LXXVIIIc = Venise 49c-51a)

- Duel between Morgan and the other witches/fairies (Koble LXXXIII = 1498:CXIXc-CXXII2c = Venise 82d-85a)

In fact, every branch of manuscripts shares material with the others, but not all, in a way that could be plotted on a Venn diagram (again taken from our article about Segurant and thus focusing on the matter of Segurant) :

Thus, Lucy Allen Paton (1927:II.348), and Ernst Brugger (1939:66), both believed, at first, that the short version came first and the other branches added episodes, but this intermingling and coherent allusions to some stories even in the short version led them to the conclusion that the original version of the Prophéties de Merlin must have included a large part of these various episodes. Obviously not everything, and Paton believed it was impossible to acertain the exact text of the archetype (called “X”) beyond a few conjectures.

Brugger wondered if the Tholomer-material might have been part of the original text, and preserved only in Vérard, Chantilly and Venise. (1937:44) In 2020, Arioli said he would investigate the matter (2020:17) — did not do it since, and has more or less said that he wouldn’t, but Véronique Winand dismissed the hypothesis after comparing the various manuscripts. (2020:188)

So Vérard might preserve some ancient material but more probably some that has been added over time. And the prophecies being out-of-order creates a lot of confusion that Matthews/Haverkamp will apparently try to solve by rearranging the material as they see fit, which will prove even more confusing.

They don’t even understand works they have rewritten

Having published rewritten stories taken from medieval texts, somehow managing to be illustrated by John Howe and prefaced by Neil Gaiman (an association that became quite less prestigious since), Matthews actually has a passing knowledge of some arthurian stories, but he manages to miss obvious points about some that he should know.

For once, the next problem resides in the interpretation rather than the translation, in a way that should be striking for any arthuriana fan:

“Write down,” said Merlin, “that from then on the knights will deteriorate in their faith as a man who approaches death. Because of the great destruction made at Salebieres, complaints will stain the honour of chivalry, since in this place both good and bad knights will die.” (p. 60, 1498:IIIr)

This is a more than obvious reference to the battle of Salesbieres, that is, as they point out, Salisbury. Since La Mort le Roi Artu, it is the last battle of Arthur, closing the enchanted arthurian parenthesis with the mutual slaying of Arthur’s and Morded’s armies, leaving only a few knights alive, the almost complete destruction of british chivalry. This is not a minor or obscure episode, we’re talking about one of the biggest setpieces in the arthurian canon, one from the Lancelot-Grail (of which the Mort Artu is part) that Matthews should therefore know. But always trying to connect things to the ancient wisdom of the druids or something, he simply remembers:

Salebiēres is almost certainly Salisbury, in which case the reference here will be to the infamous “Night of the Long Knives,” which took place at Stonehenge and in which many British chieftains were killed after being lured there by the Saxons under a flag of truce.” (p. 60)

The cloister of Ambrius, near Salisbury, is the setting for this other scene in the Historia Regum Britanniae, (IV.15) where Hengist has 460 british princes assassinated by surprise and they are buried near Salisbury. But the prophecy obviously discusses the final battle of Salesbieres, and the killing of good and bad knights that took place.

They do not recognize the adventure of Alexander the Orphan, another nephew of king Mark:

“A message was conveyed to the Queen of Norgales and Sebile, who were in the castle of Norgales. They were told that Morgain had brought a wounded knight to Belle Garde.” (p. 119)

The note adds : “This probably refers to Lancelot. In a famous episode from Le Morte D’Arthur, he is captured by the three queens, each of whom attempts to seduce him.”

The kidnapping of Lancelot does happen in the Lancelot proper in the Vulgate (Lancelot-Grail). It has indeed been taken up later by Malory. That said, here it refers to the adventures of Alixandre l’Orphelin, Alexander the Orphan, that are found in the long version of the Prophéties de Merlin and some compilations and versions of the Prose Tristan. (Our review, in french, of Arioli’s translation has a table of the episodes across the manuscripts.) His kidnapping by Morgan is indeed inspired by the same adventure happening to Lancelot in previous texts. His episodes are covered in Paton’s summaries (I.375 sqq., 403 sqq., 413 sqq., 415 sqq., 421 sqq. etc.) — so Matthews&co haven’t even read that? For the episode in question :

The day after the tournament the damsel tells Alisandre that if he desires the country to be at peace, he must do combat with her neighbor, Malgrin le Felon. As they talk Malgrin rides up and asks Alisandre if he intends to marry the maiden. Alisandre replies that he shall do as he pleases, whereas Malgrin defies him on the ground that he is too orgulous. They engage in a deadly combat in which Malgrin is unhorsed. They continue the struggle with swords, until Alisandre fells Malgrin to the ground mortally wounded, and cuts off his head. He himself sinks to the earth, weakened from loss of blood. As he lies there, Morgain comes to him and promises to heal him. He is carried into the castle, where Morgain follows him and binds his wounds with an iritating salve that mcreases his sufferings ; the next day, after having won his promise to do her bidding if she relieves him, she anoints his wounds with a healing ointment. The mistress of the castle begs Morgain to induce Alisandre to marry her, and Morgain to prove her own sincerity bids her come to the bedside of Alisandre and listen to her entreaties ; but Alisandre, having already promised Morgain that he will not marry the maiden, refuses now to do so and assures her that, as the custom requires, he will give her to another knight. The maiden chooses Guerin le Gros as the substitute for Alisandre, and the following day, Alisandre goes to the great hall, where she and her attendant damsels are assembled, and formally presents her to Guerin. Great rejoicings in the castle follow, and Morgain offers to take Alisandre in her litter away from the noise of the festivities to a pavilion that she has had spread for him. As soon as he is in her litter, she drugs him, and while he sleeps she conveys him to her castle, Bele Garde, where she keeps him till he is healed of his wounds. Then he begins to chafe at his confinement and to feel heavy of heart. ‘‘Mes atant lesse li contes a parler de ceste aventure et parole de la court le Roy Artus et de la Dame d’Avalon que Merlin envoia en Yrlande au tens que il vivoit.” (Paton I.413-414)

This becomes even more baffling when a following section is restituted, not from any manuscript, but from Paton’s summaries.

Vérard’s edition has a few episodes from the long version, often incomplete, and the authors correctly feel that they can complete one of them with texts from the rest of the tradition, but make this baffling choice of not looking for the original text and just putting some summaries from 1926, lightly rewritten. (Paton 1926:I.372-3 = Matthews/Haverkamp chapter 82, p. 121-123)

“The story of the feud between the faery women is continued in the 1303 Rennes manuscript of the Prophecies as edited by Lucy Allen Paton. The following sections are drawn from Paton’s summaries of the episode, found in Paton, Les Prophecies de Merlin; Part Two: Studies in the Contents.” (p. 121n141)

Even this is not true! The summaries come from the first volume of Paton’s edition, part one “the Text”, section IV, summaries of the episodes of group I, not the second volume, Studies in the Content. How do you even mess this up! How do you rewrite summaries without reading them and misquoting from which volume they come? How?

They don’t even seem to understand when they draw from the long version, or the place of the Rennes manuscript in it. Even if the quality of the text might justify its use as a base manuscript, the Rennes manuscript is actually unusual, being an abridged manuscript of the long version, containing shortened versions of the romance storylines. As such, the summaries refer to the folios of manuscripts E (Bodmer 116), BnF 350 and BL Add. (eg. I.11) which contain the full stories. The Bodmer 116 is the most complete manuscript of the long version, but at the time of Paton’s edition it was in the grasp of Maggs Brothers and she did not get the permission to edit it. (Paton 1926:I.9, I.51) Thus why she resolved to focus on Merlin’s prophetic storyline and only give summaries of the Arsenal and long version episodes, even if quite complete summaries.

“It seems quite extraordinary that this book has lain almost forgotten for so many years. Eighteen copies of the various manuscripts have seldom been explored, and only one other edition exists, in medieval French—that of Lucy Allen Paton.” (p. 233)

This was true in 1927, but the Bodmer 116 has been edited by Anne Berthelot in 1992, and by Nathalie Koble in 1997-2001, the text of her thesis’ edition even being available online since december 2023. The edition is quite literally freely available on the internet, but the authors seem completely unaware and thus their “translation” reworks summaries of texts that have already been edited twice.

While not clearly indicated beyond the fact that paragraphs sometimes are in between quotes (unexplained), chapters 66-67, 69, 75-78 and 83-84, are also straight up copied from Paton’s summaries (see Paton I.414-420 ; I.407-410 ; Paton I.372-392), with mistakes added of course. For exemple they quote the transition formula “Mes atant lesse li contes a parler de ceste aventure et parole de Richarz de Jerusalem” from the summary of Paton (I.407) but translates it

Merlin said: “I now take the opportunity to speak of the adventures and words of Richard of Jerusalem.” (p. 114)

This is wrong, the actual translation would be Now the tale ceases to speak of this adventure and speak [instead] of Richard de Jerusalem.

This actually becomes even denser for chapter 77, Of the King of Ireland and King Baudac, because they simply copy the summary of the long version in Paton (I.409)… but this is actually one of the few episodes of the long version partially extant in Vérard’s edition. So the text can actually be found fol. LVIIa-LVIIIc. Same goes for other scenes of the “fairy women” storyline. Missing the existence of the long version, I can figure out how that happens, but missing text that is actually in the edition you’re supposed to translate? That’s art right there.

Sometimes, the authors seem as puzzled as me, maybe because of great teamwork. Before chapter 66, a note says:

“It is not clear whether the section that follows is in the voice of the author. We have assumed it is still the voice of Merlin.” (p. 104)

That’s because the following text is quite obviously a summary with a brutal tone shift, but apparently the person that ripped it from Paton forgot to tell the one in charge of the commentary.

I’m also under the impression that chapters 42 to 45 have been translated from Paton I.178-181, but unsure. An even more puzzling case comes from chapter 78, which starts like Paton CCCI, a Damsel brings her son that has been transformed into a deformed mass of flesh by her sins, because she had slept with the knight that killed her father. But she puts a ring that an hermit had preserved from said knight, now dead,, that had told him he wanted to marry her. When she puts on the ring, her child is apparently blessed by the power of Marriage and becomes a beautiful young man. (By the way, Valet should be translated here as young man and not footman/servant as in modern french.) But our geniuses at Matthews&co betray even more reading mistakes than usual and a really weird ending. From their version :

While she spoke thus, an old man came by who turned out to be a hermit. He had a gold ring with a gemstone in it. The hermit must have followed her. He gave her the ring and said that Merlin asked him to give it to her when he was one hundred years old, so that the ring would bring her fame. Then they returned to King Arthur’s palace, and the maidservant led the girl to her room. What shall I say? The damsel was clad in the king’s relined mantle. When the king went to the damsel, he took the ring in his hand and put it on his finger. What Merlin had said while imprisoned in the tomb is fulfilled: King Arthur and Guinivere were married.

That has absolutely nothing to do with the text from Paton. I don’t think it’s supposed to be in Vérard’s edition (but I have mostly given up at that point) and don’t know where all the stuff about this being Arthur and Guinevere’s wedding comes from but, if I might hasard a guess, it could fit the type of hallucination that some LLM could produce while translating badly transcribed text… Then the end:

On the following morning the High Prince Galeholt prepared for the tourney, which began when the knights were armed and Queen Guinevere and her ladies were in their places. After a fierce battle between the Knights of the Round Table, Lancelot emerged victorious. In the city of Vitré the good knights began their quest for the Holy Grail.

Not sure where this comes from either.

(Also “Li rois Blans fu mon pere et la roinne d’Arians fu ma mere.” becomes “The White King was my father, and the Queen of the Aryans was my mother”… it’s a common thread in occultism but they generally try to be more subtle.)

Even beyond the complicated tradition of the Prophecies de Merlin they mess up the arthurian canon, as we have seen around the death of King Lot. In their introduction they also situates the tradition of Merlin’s prophecies in the wider arthurian canon, Geoffrey and the welsh tradition, from which some texts are translated in an appendix. (Having lost faith in humanity I didn’t bother to check these translations.) But they seem to skip from the Vulgate (Lancelot-Grail) to Malory, forgetting the Post-Vulgate texts where a lot of this develops. Eg. :

“In Le Morte D’Arthur, Sir Thomas Malory’s fifteenth-century reworking of parts of the Lancelot-Grail (or Vulgate) cycle and other texts, the confusion amongst the Lady of the Lake, her handmaiden Nimuë, and Morgain becomes profound. The Lady and Morgain, whose functions are so similar in early tradition, become mutually antagonistic. »

This opposition actually appears in the “Post-Vulgate” Suite du Merlin, where Morgan attacks Arthur (through the Accalon plot, for example) and the Lady of the Lake try to protect Arthur with her powers against her plots. This was from then taken up by Malory.

This might seem a scathing review, but it could be extended to the whole book with the same vitriol, although I have better things to do than catalogue the absurdities assembled there. You might tell me, errare humanum est, after all, it is a complicated subject, and many an honest scholar would do some mistakes of the same nature, maybe I shouldn’t be too harsh about this failed attempt at bringing a fascinating book to the public. My translations here probably contain errors as well, as well as my understanding of the manuscript tradition. Thus, beyond the question of ignorance, I want to conclude on their atrocious lack of curiosity, a strange choice announced at the beginning of the book :

“We also chose to omit certain of the prophecies, which were either entirely religious or politically motivated and which have little or no relevance to a modern audience.” (p. 17)

Why? If you do not care about religious or political propaganda, why would you want to translate a text that, in large part, seems to be the work of a joachimite that somewhat believes that Frederic II is the Antichrist and that Venitians are the good guys? If you do not care about such things, why are you doing this? Why are you inflicting your half-baked “reflexions” about something you simply cannot be bothered to learn onto the innocent reading public?

Paradoxically, you will have noticed that they do translate prophecies about the religious or political climate of Italy in the thirteenth century, notably those mentioning the thing coming from parts of Jerusalem, but, here’s the thing: they didn’t understand them, and thus weren’t able to cut them. They were looking for anything vaguely mysterious and mystical, and when you understand so little everything appears veiled in a deep mystery. It becomes quite easy to live in an enchanted fairy-world where telz is not a simple french word but obviously a baltic city full of heretics. Mount Gargans must be Saint Galgano which must be the Sword in the Stone. Writing prophecies in stone is like Moses coming down with the tables of the law from Mount Sinai. Squint your eyes hard enough and anything interesting can be retrofitted into mystical nonsense.

Table: Correspondance between the « translation », Vérard’s edition and Paton’s (WIP)

Incomplete but left as an exercise to the reader.

| Matthews chapters | Paton edition | Vérard 1498 |

| 1: Merlin Begins His Prophecies | Ir | |

| 2: Of the Sea That Will Grow above the Shore as High as the Mountains | [reproduced in Paton 450 sqq.] | Iv–IIIr (then cuts) |

| 3: About the Dragons That Live Underground | fol. CXLIIv-CXLIIIr | |

| 4: The Queen of Brequehem Visits MerlinQueen of Brequehem mentioned in Paton LXXI sqq. = Vérard LXVI sqq. but not the same episode | ? | ? |

| 5 : [cut and placed at chap.74] How the Emperor of Rome Came before the Pope with a Hundred Knights | [reproduced in Paton 475-6] | fol. XXVI. |

| 6: The Death of King Arthur | ? | ? |

| 7: Of the Damsel from Wales Who Came to the Room Where Merlin and Tholomer Were | Paton III | end of IIIra. |

| 8: Of Master Richard, Who Translated Merlin’s Prophecies (from Paton’s edition) | Paton 76 before chap.XVIII | – |

| 9: Of the Crown of the Emperor of Orbanc | Paton XIV | LVII? |

| 10: Of the Crown of Orbance That Shall Be Found | Paton XVII | LVII? |

| 11: How a Large Part of India Will Melt | Paton XIX | fol. CXXIIv |

| 12: Of the Evil Lady of Falone | Paton XXII | fol. CXXIIIr. |

| 13: Of the Macedonian Wolf and Other Things | Paton CII | fol. LIXr |

| 14: Of Muhammed Who Built a City in Three Days | = without the three days in fol. LIXv ? | |

| 15: Of the Good Mariners | Paton LIII | fol. LVIIIv |

| 16: Of People Who Go on a Pilgrimage to the Sea with the Emperor of Rome | Paton XCIII ? | fol. LXXX? |

| 17: Of Merlin Alerting Master Antoine to the Arrival of the Three Ministers | Paton XXXIX | fol. LXr |

| 18: Of the Lady Who Came to Antoine’s Room | Paton LXI | LXXX ? |

| 19: Merlin Speaks Regarding the Lady of the Lake | Paton LXII | |

| 20: Of the Lady of the Lake and of Lusente | ||

| 21: How Merlin Went to the Forest of Avrences | ||

| 22: How Merlin Bade Master Antoine Farewell and Entered the Forest of Avrences Where the Lady of the Lake Was | fol. LXXXVI | |

| 23: How Merlin and the Lady of the Lake Got to the House Where Merlin felt at Home | fol. LXXXVII | |

| 24: How Merlin Lived with the Lady of the Lake for Fifteen Months | fol. LXXXVIII | |

| 25: Of the Lady of the Lake, Who Fooled Merlin While She Slept with Him | ||

| 26: Of the Lady of the Lake, Who Decided to Cheat on Merlin | ||

| 27: How Merlin Went with the Lady of the Lake to the Tomb in the Rock | ||

| 28: Of Merlin Lying in the Tomb, He Died More Each Day | ||

| 29: Of Merlin’s Ghost, Who Will Speak to All Who Come to His Tomb | ||

| 30: Of the Departure of the Lady of the Lake | fol. LXXXVIII | |

| 31: Of Merlin Speaking to Meliadus, Friend of the Lady of the Lake | fol. XXXI? | |

| 32: Of Merlin Telling How His Father Killed His Mother | ||

| 33: Of Tristan, the Brother of Meliadus | ||

| 34: How Meliadus Went to Church and Found Letters Testifying to What Merlin Had Said to Him | ||

| 35: How Meliadus Left Merlin and Came to Wales | fol. XXXII? | |

| 36: How Meliadus Departed from King Arthur’s Palace and Met the Lady of the Lake | ||

| 37: Of a Knight from the Land of the Indies Who Came before the Chaplain | ||

| 38: Of the Woman Who Did Evil to Her Husband | ||

| 39: How the Lady Rambarge Pretended to Feed Merlin but Wanted to Kill Him | CXLIX? | |

| 40: How the Lady Rambarge Tried to Strangle Merlin | CXLIX? | |

| 41: Of Merlin’s Message to Naymar | CLIX ? | |

| 42: Concerning the Lady of the Lake, Who Sent a Reply to the Queen about a Dream She Had Dreamed | Arsenal (48va-49rb Koble XVI (Bodmer 116 fol. 33rb-35n) = Paton I.178 hors Rennes | Seems to be translated from Paton as 1498 cuts after Koble XV = fol. XXVv? |

| 43: Concerning the Dream That the Queen Dreamed | Paton I.180 | |

| 44: Concerning the Stone the Lady of the Lake Gave to the Queen | Paton I.180 | |

| 45: How the Queen’s Damsel Asked Sebile the Sorceress to Explain Her Mistress’s Dream | Paton I.180-1 | |

| 46: Prophecies Found by a Knight on a Stone Written by Merlin | Koble CII | fol. CVI |

| 47: Meliadus Was So Serious That He Swore to Kill Any Knight Who Passed through the Forest | Koble CII | fol. CVI |

| 48: Of the Letters Merlin Carved in the Stone | Koble CII =Paton 315-329 ? | fol. CVI |

| 49: The Importance of the Letters on the Stone | Koble CII | fol. CVI |

| 50: Of Meliadus’s Meeting with the Wise Clerk and His Departing from King Arthur’s Palace | ? | |

| 51: How Meliadus Was at Merlin’s Tomb, and of the King’s Son, and of Tristan | Fits more with Paton CXLV (quotes) | Seems CXXV-CXXVI but quite garbled |

| 52: Of an Angel Who Will Take Water from a Fountain and Extinguish a Fire at the Castle of Morgain | fol. CXXVI | |

| 54: How King Henry and One Hundred and Fifty Knights Will Go to the Forest of Avrences | fol. CXXVI | |

| 55: On the Death of Tristan and How Meliadus Cannot Harm the One Who Killed Him | XX-XXI (completely garbled and cut) | |

| 56: Of Raymon the Wise Clerk of Wales | ||

| 57: Of the Damsel Who Visited the Chaplain | CL? | |

| 58: From the Clerk Who Came before the Chaplain | CL? | |

| 59: Of the Enemy Who Broke the Brazen Image | CLI | |

| 60: Of the Sad March of the Lady of Caiaphas | CLI | |

| 61: Of Those Who Cannot Be Buried until the Third Day | CLII | |

| 62: Meliadus Alone Has Access to the Tomb | ||

| 63: Of the Wise Clerk of Wales, the Enemy, and Percival | Paton CLXXXVII? | |

| 64: The Round Stone Goes to India | ||

| 65: The Wise Clerk Goes to Meliadus | ||

| 66: The Plots of King Marc against Tristan | From the summary of Paton I.414-415 | |

| 67: The Release of Tristan by Percival | From the summary of Paton I.417 | |

| 68: The Deaths of Tristan and Yseut | ? | ? |

| 69: The Plot of Claudas against Lancelot | From the summary of Paton 420-421 | |

| 70: Of the Damsel from Avalon Who Came in a Boat | fol. LXXXIX | |

| 71: King Arthur and the Maiden of Avalon | fol. XCv | |

| 72: Of the Letter That the King of India Sent by the Maiden of Avalon to King Uterpendragon | Paton CCLXV | XCIr but not the end? |

| 73: Of the Proud Damsel of the White Kingdom and King Arthur’s Wedding | Paton CCCI Koble XCVI | ? |

| 74: Of the Emperor of Rome, Who Came before the Pope with a Hundred Knights | fol. XXVI. | |

| 75: Of the Aid Sent to Jerusalem | From the summary of Paton I.407 | |

| 76: Of Richard of Jerusalem | From the summary of Paton I.407-8 | |

| 77: Of the King of Ireland and King Baudac | From the summary of Paton I.409 | LVIIa-LVIIIc but not taken from there as they use summaries, apparently not knowing it is partly in Vérard. |

| 78: Of King Arthur and the Knight of Carmelyde | From the summary of Paton I.409-410 | |

| 79: How a Lady from Abiron Put Merlin to the Test | Paton LXV | |

| 80: Of the Ring Merlin Gave to the Lady of Abiron | Paton LXVI | |

| 81: The Lady of Avalon, the Queen of Norgales, Sebile, and Morgain | CXIX-CXXII | |

| 82: On the Rescue of Breuse Sans Pitie (from Paton) | Paton I.372-3 | |

| 83: Of Berengier de Gomeret | Paton I.388 | |

| 84: The Reconciliation of Morgain and Sebile | Paton I.392 | |

| 85: How Helias Gave the Book of Blaise to Percival | ||

| 86: Of Percival’s Search for Merlin’s Grave and His Several Adventures | CIX | |

| 87: Of the Death of the Hermit | ||

| 88: On Rubens, Who Took the Place of Raymon the Wise Clerk of Wales | CXLVII | |

| 89: The Death of Raymon the Wise Clerk of Wales | CXLVIII | |

| fin |